Bayesian Statistics

What we have discussed this semester is known as the frequentist approach to statistics, but another approach is called Bayesian statistics. Two lines of argument show the rationale for taking a Bayesian approach.

First, recall what we calculate in frequentist statistics. We calculate a p-value, which is the probability of observing a given statistic (or a more extreme value) if the null hypothesis is true. We also calculate likelihoods, the probability of observing of given statistic if some hypothesis is true. Both of these might strike you as backward in that we are using what is unknown (whether the hypothesis is true or not) to make inferences about what we already know (the observed statistic). What we’d really like, though, is the opposite: we’d like to know the support for a hypothesis provided by the data.

Second, the way we go about hypothesis testing in the frequentist framework is that every test stands on its own, but that’s not how we work as scientists. For example, suppose you perform a statistical test on natural selection. If you reject it, saying that the data are not consistent with natural selection, it’s not as if the entire edifice of evolutionary theory crumbles. It’s just one piece of evidence, one that happens to conflict with an enormous body of previous evidence in support of natural selection. What would be better is if our approach could explicitly consider this previous work and reevaluate the hypothesis in light of our new data.

Bayesian statistics provides for both, a way to measure the support for a hypothesis given some data and a way to evaluate how the support for a hypothesis changes in light of a new experiment.

Although Bayesian statistics has been around as long as frequentist statistics, Bayesian methods have become much more common in the past decade. Statisticians are often sharply divided between frequentists and Bayesians, and the arguments are commonly heated.

Bayes’ Rule

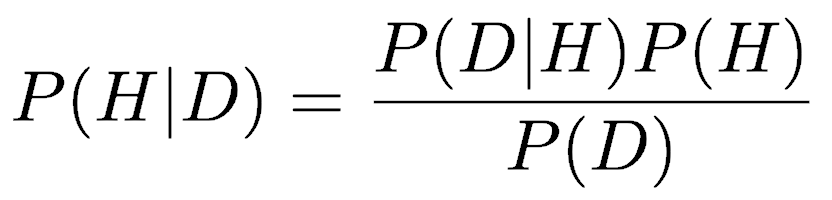

The core of Bayesian statistics lies in applying a relationship known as Bayes’ Rule:

Bayes’ Rule links four probabilities. P(H) is the probability that the hypothesis is true. P(D) is the probability that our data would exist. The remaining two probabilities are conditional probabilities, that is, they are probabilities contingent on something else being true. The first, P(D|H), is the probability of observing the data if the hypothesis is true, what is called likelihood, and is the start of calculating a p-value. The second, P(H|D) is the probability that the hypothesis is true given the data we have collected.

We will use Bayes’ Rule to convert from what we have been calculating, P(D|H), to what we would really like to know, how well a given hypothesis is supported, P(H|D).

An example

Bayes’ Rule can produce some insightful yet initially counterintuitive results, which is one of its attractions. Interpreting medical test results is one common example.

Suppose a person had a mammogram to screen for breast cancer and received a positive test result. A positive test is alarming, and it should always be taken seriously, but Bayes’ Rule can put those results in perspective.

Using Bayes’ Rule from above, we can think of the hypothesis (H) that the person has breast cancer, and the data (D), the positive mammogram test results. What the person would like to know is the probability that they actually have cancer given that the test was positive.

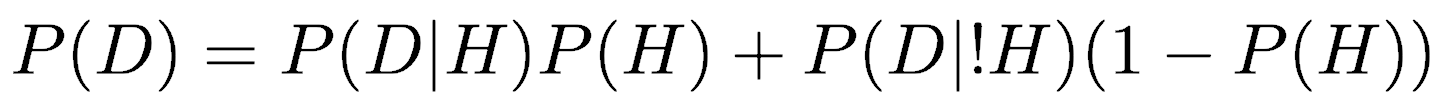

After searching the medical literature, we find some recent data we need (Nelson et al. 2016). First, the disease is relatively rare, with 2,963 cases out of 405,191 women screened. Thus, the probability of having breast cancer—P(H)—is about 0.0073. Second, mammograms produce false positives (indicating cancer when there is none) at a rate of about 121 per 1,000 women. Thus, P(D|!H), the probability of getting a positive mammogram result when a person is cancer-free is 0.121. Third, mammograms produce false negatives (where the mammogram fails to detect cancer in a patient who has cancer) at a rate of about 1 in 1000. Thus, P(D|H) is 1 - (1/1000), or 0.999. These give us directly the two terms in the numerator of Bayes’ Rule, P(D|H) and P(H), and the ability to solve for the denominator, P(D).

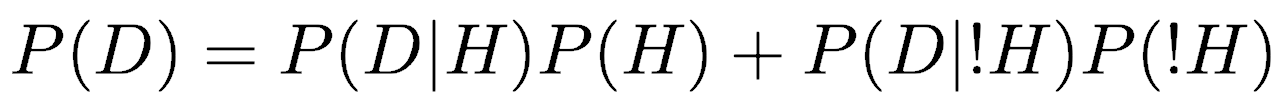

Finding the probability of a positive result on a mammogram, P(D) is more complicated. We must consider the two possible states: having cancer (H) and not having cancer (!H). Importantly, these are mutually exclusive: you can’t simultaneously have breast cancer and not have it. Therefore, the probability of the data (a positive mammogram result) is the sum of the probabilities of those two states, each multiplied by the probability of a positive mammogram result data given that state:

Furthermore, because the two states are mutually exclusive, we know that the sum of their probabilities is one, so we can make a substitution for P(!H):

Substituting the probabilities, we get:

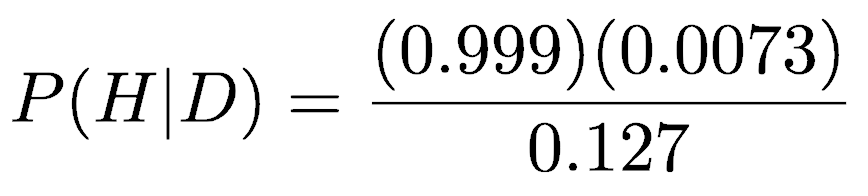

Simplifying gives P(D)=0.127. We now have the three terms to calculate P(H|D) from Bayes’ formula.

Solving for P(H|D) gives 0.057: there is only a 5.7% probability that a woman who tests positive on a mammogram actually has cancer. This is still of course serious, but it is a good reminder that the odds are still in your favor if you test positive.

Less seriously, Bayes’ Rule is helpful in solving the Monty Hall problem.

Application

Using Bayes’ rule for statistics presents two problems. First, we may not know the probability of observing our data, P(D), especially when it is not contingent on any particular hypothesis. Second, we don’t know the probability that the hypothesis is true, P(H); moreover, that is what we would ultimately like to know.

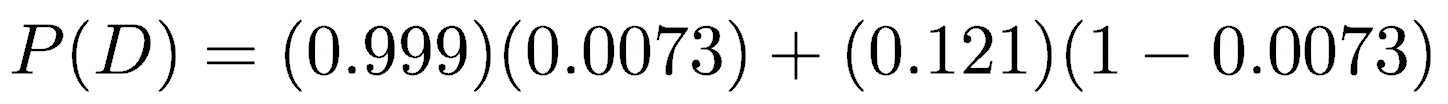

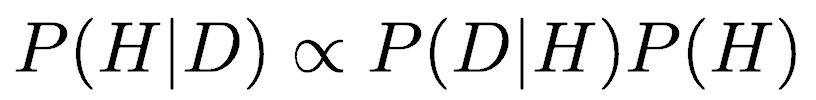

Because the probability of the data, P(D), will be the same regardless of what hypothesis we are evaluating, we could treat it as a proportionality constant. This lets us rewrite a simplified Bayes’ Rule:

Furthermore, we can set the probability of the hypothesis, P(H), to reflect our current knowledge about the hypothesis, and it is therefore called the prior probability, or simply, the prior. Similarly, the term P(H|D) is called the posterior probability, and it is the result of the product of the prior and the likelihood, P(D|H). In other words, this simplified version of Bayes’ rule gives us the support for a hypothesis after we have collected the data (that is, the posterior probability) based on our support for the hypothesis before we collected the data (the prior probability) updated by the likelihood of the data given the hypothesis. Bayesians like this formulation because it is an analogy of how we do science: we update our existing view of the world as new data comes in. New data may result in a different hypothesis becoming our favored model of the world.

To a Bayesian, probability does not have a frequentist interpretation, that is, it is not equal to positive outcomes divided by possible outcomes. Instead, Bayesian probability is measures the degree of belief in a hypothesis. In a frequentist’s view, one cannot talk about the probability that a hypothesis is true; it is true, or it is false, we just do not know which. Indeed, in the frequentist concept of probability, discussing the probability of a hypothesis makes no sense, so. frequentists instead talk about the probability of an outcome assuming a hypothesis is true. Bayesians, however, always talk about the probabilities of various hypotheses, and by that, they mean the support for those hypotheses. Bayesian probabilities indicate the various degrees to which the hypotheses are supported not only by the data but also by our prior knowledge. For scientists, this is an appealing way to think about our task.

It should be obvious that the posterior probability depends just as much on the prior probability as on the likelihood of the data given the hypothesis. It is possible to set the prior probabilities such that no new data could change your view of a favored hypothesis, but this is not legitimate. You could set the prior probabilities to be the same across all models, and these are called uninformed priors, weak priors, or flat priors. When you do this, the posterior probability is controlled only by likelihood, so using weak priors is the same as using likelihood. Moreover, not considering prior probabilities makes the approach the same as what frequentists do: starting from scratch every time, never incorporating prior information on the strength of a hypothesis. Bayesians, on the other hand, see it as essential that you include prior knowledge when you evaluate a hypothesis. Bayesians are split into two camps on how these prior probabilities should be established. Objectivists view prior probabilities as coming from an objective statement about knowledge. Subjectivists view prior probabilities as coming from personal belief, and this approach is disconcerting to many scientists.

References

Bolker, B.M., 2008. Ecological models and data in R. Princeton University Press, 396 p.

Hilborn, R., and M. Mangel, 1997. The ecological detective: Confronting models with data. Monographs in Population Biology 28, Princeton University Press, 315 p.

Nelson, H.D., E.S. O'Meara, K. Kerlikowski, S. Balch, and D. Miglioretti, 2016. Factors associated with rates of false-positive and false-negative results from digital mammography screening: an analysis of registry data. Annals of Internal Medicine 164(4):226–235.